No Two Gardens Are Alike

"Why" is just as important as "how" in developing our own gardening practice.

Recently, a note appeared in my Substack feed that made me reflect on why I’m doing what I’m doing here. The author was lamenting gardeners’ publications focused on how-to, which I totally understand. It’s actually the garden stories that are important, because no two gardens are alike. Neither are any two gardeners. My 40 years of experience have taught me this: The how-to’s are less important than the why’s, but they do belong together, because our stories are derived from our practice.

We all have our ways of doing things and that set of methods makes up our own unique practice. Like any practice, a gardener’s way of doing things is influenced by traditions, understandings, and personal experience. Importantly, it is informed by the knowledge and values of the practitioner. If it is to be considered professional practice, it is also based on research and best practice models that have undergone the scrutiny of fellow professionals. We expect of professionals that they are able to explain why something is more or less effective. “My grandmother always did it that way,” is an absolutely valid explanation, but it is not professional. What interests me is why grandma’s method worked and in what context, because, well, context is everything.

My first knowledge and skills in vegetable growing were acquired 50 years ago on a small family farm in Wisconsin. They were derived from following my father’s practice (plow, disk, till, sow in rows, weed and till, weed some more). Indirectly, I was also influenced by Mother Earth News, a magazine started in 1970, at the peak of the back-to-the-land movement of the time. Its focus was on ecology and DIY and “the original guide to living wisely” covered everything from hunting to building, gardening to beekeeping. Sustainable living was at its heart, but a white American male identity limited the scope of context as well as knowledge and skills it portrayed. It has surely gained in popularity with the current homesteading trend in the United States. Their website is full of free guides, from everything to enjoying the outdoors to companion planting.

My father saved all of the issues, stacked up next to his easy chair, so I’m quite sure Mother Earth News was the source for building plans for the cold frame we had on the south side of the house. I can see it so clearly in my mind’s eye, the chipping white paint, the old four-paned window propped up with a stick on sunny spring days. Indoors, he started tomato seeds on the windowsills on that same south side, which had been my grandparents’ formal parlor and then our living room. At some point, the leggy seedlings were potted up and put in the cold frame. Due to the short growing season, we only had determinate tomatoes, mainly for canning. I learned about indeterminate tomatoes and staking them years later.

Because of all that plowing and tilling, the weed pressure was enormous. As of about the age of 10, my job was to keep the quarter-acre (1000 sq m) family garden as weed-free as possible. While I weeded the rows by hand, my father would till the paths when they got bad enough, i.e., when a mower would have also done the job and improved soil health at the same time. His realm was machines, not manual labor. In the early 1980s, when I was in high school and earning money at part-time jobs, he lost his gardener and the weeds took over. Conveniently, glyphosate had appeared on the market. He sprayed it everywhere and much of the property turned brown.

I mention this last bit because what might sound romantic - a farmer reading Mother Earth News and raising his transplants in his DIY cold frame - was anything but. His practice was driven by one goal: easy work. He had a wife who canned and froze and otherwise processed the astounding abundance of food each year, then prepared it and brought it to the table. His time gardening was nothing in comparison to the hours my mother spent feeding us.

Striving for easier and less work

I confess that my goal as a (market) gardener is also easy work, but in a very different way. First of all, my values ban the use of herbicides and pesticides, even those approved for organic farming. Glyphosate is easy to avoid, if you don’t turn over the soil and free new weed seeds. I don’t even own a till, nonetheless a tractor, which has become a positive now that I’ve studied soil ecology a bit. Instead of tilling, I start a garden with occultation (tarping) and compost, aerate the soil once a year with a broadfork, and use the fresh-cut grass from the living pathways as mulch. Even more sustainable is my current practice: In an effort to reduce compost, I successfully started my second market garden with spent silage and digestate, the by-product from a bio-gas facility. These materials are practically weightless and easy to haul and spread over new beds. After two months of tarping the thick layer (20cm / 8 in), the beds are ready for transplanting or sowing, although sowing is a bit tricky with the thick layer of mulch in the first year.

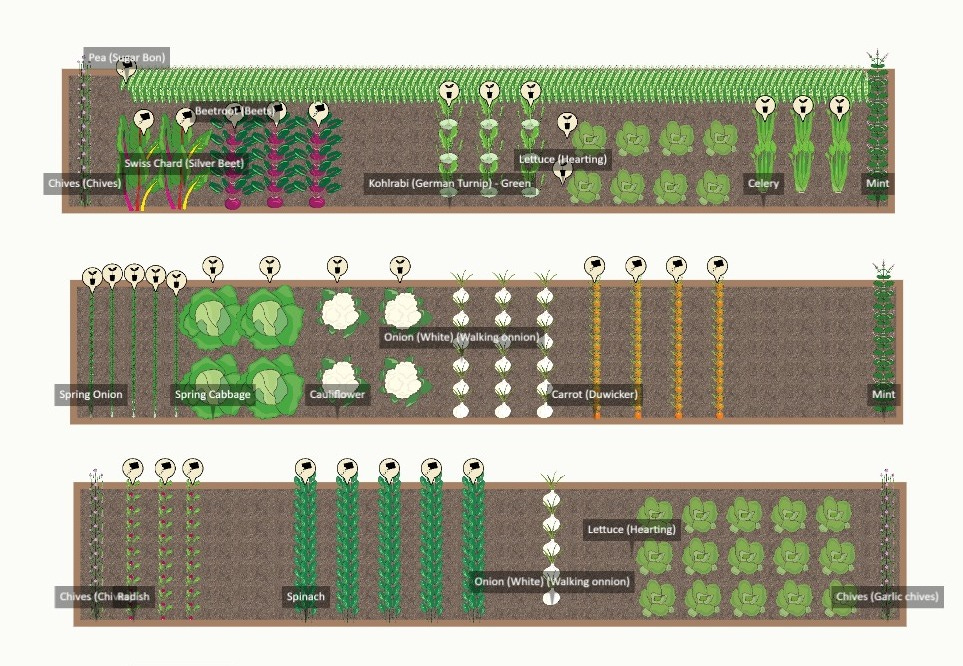

Another method I use to reduce hard work and save time: broadcasting seed whenever possible. I’m not as radical as the queen of “no-work” gardening Ruth Stout was, although I do sometimes try to channel her when planting potatoes. (I have trialled her straw method for potatoes, by the way, and find old-fashioned in-ground planting to be more productive.) My garden beds are usually 100 cm / 40 in. wide, perfect for me to easily sow, plant, tend and harvest without stepping all over them and compacting the soil. This bed size also allows me to plan by the square meter, which is similar to square foot gardening, with the advantage of enabling more interplanting. (For non-metric folks, think by the square yard.)

As a result, I think in groups by square meter, not rows. Rows are not necessary for carrots, radishes, beets, spinach, leaf lettuce, and they are easy to broadcast. Let me repeat that: Rows are not necessary. Row culture is oriented to machines like tillers and tractors. It also makes hoeing easier if you have a weed problem. Tilling causes weed pressure, ergo: Minimal tillage, minimal weed pressure. (If you’re wondering about whether or not to till, I recommend Taylor Myers’ recent piece entitled “Should I till my garden?” It is a wonderful, knowledgeable response to this question.)

Of course, broadcasting requires a trained hand to avoid seeding too densely, but this, too, can be trained and in my context takes less time and expense than callibrating a finicky seeder that requires a bed to be prepared just so in order to function. (Been there, done that.) When I broadcast, I lightly work the seeds into the surface with a garden rake, moving it up and down to agitate the surface and help the seeds settle into nooks and crannies. Broadcasting makes most sense when there isn’t a heavy mulch layer (although that didn’t stop Ruth Stout) and beds are weed-free. Larger seeds, such as beans and peas, I still sow in rows at the appropriate depth.

Market gardeners, especially those working with a no-till approach, have developed a “stale seed bed” strategy. When a bed is harvested, it’s covered with tarp for two to three weeks to kill off anything growing or emerging. Others with weed pressure sow their carrots and then flame-weed just before the seedlings emerge. I prefer tarping, if necessary, because flame weeders use propane gas and I try to keep my use of fossil fuels to a minimum. Occultation can also be used by home gardeners, if blocks rather than rows are used in the garden plan. It’s relatively easy to cover a square area with cardboard weighted down with stones or boards for a couple of weeks.

As I hope has become clear, a lot of unlearning and retraining, questioning and reading has been involved in developing my garden practice over the last 40 years or so, and I continue to improve it. I’ve changed contexts enough to know that what works in one situation might be a disaster in another. As a garden coach, I also am acutely aware that my prescriptions can fail for another gardener in a different context. These days, as I close in on my 60th birthday, my focus is on developing strategies that are as sustainable for me as they are for the environment.

My advice:

Celebrate your unique context, whether it’s an apartment balcony in a city, a small patch in suburbia or a field in the country, and work with it responsively. (By the way, those growing vertically or in container gardens will learn much from Vertical Veg: Container Gardening by Mark Ridsdill Smith.)

Seek answers by asking the why-questions: Why this way? Why is this happening? Why did this (not) work?

As for me, I’m here as a gardener and a teacher for you, because I’m both by trade. The how-to’s are less important than the why’s, but they do belong together.

What I’ve been doing this week:

A note about context: I live in Zone 7b/8a based on the last couple of years here, but that doesn’t say much. The USDA zones refer to high and low temperatures to determine which perennials will survive there. Of greater relevance is my frost dates: Generally, by mid-April it is frost-free, but a late-spring frost in early May is common. The first frost is sometime early November, but an early frost can occur mid-October.

We’ve just hit the 10-hour mark here in southeastern Austria, which means our daylight is now enough to encourage growth. Eliot Coleman, the master of winter harvest, dubbed the dark days of winter with less than 10 hours of daylight the “Persephone Days,” named after the goddess of spring, flowers and youth whose annual return to Hades in winter caused the earth to become barren.

I’ve started my plant production this week, which is always exciting, but also a bit terrifying, when I see how much I sow as a market gardener. For home gardeners, you can cut this work down a lot!

I’ve sown the following in seed trays, to be potted up when the seedlings develop their first true leaves:

lettuce (needs light to germinate)

bulbing onions

leeks

celery

bulb fennel

peppers

chilis

eggplant

The following are in deeper seed trays, because I will plant them in groups of three without potting up in between, and I want their roots to have room:

bulbing onions

leeks

The following I’ve sown in flats of 77 cells, each cell 4 cm/1.5 in., to plant out in late March:

bunching onions, groups of 7-10

parsley, groups of 3-4

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what was helpful or new to you - suggestions for topics are always welcome. Remember: This weekly newsletter is free and by subscribing you not only support but also motivate me.

Great post Tanja, it's so nice to see really experienced gardeners share their trial and error stories. We have also tried a few things like the potatoes in straw in one of our projects and found it gave us very few potatoes!

What a lovely response. Thank you! I sometimes "share" seeds with starlings, the little buggers. And thank you for your Substack! I really enjoy it.